What is a raster image? File types and their hidden superpowers

Tuesday, October 27th, 2015

What is a raster image? What other kind of image is there?

You might think that a picture is a picture but when it comes to using your images in print or on the web, there are some very important distinctions to be made. The most important of these distinctions is between vector images and raster images.

What are vector graphics?

A vector graphic isn’t an image so much as a mathematical recipe for building the image and doesn’t have any limitations in terms of size. Vector graphics are infinitely scalable–if you have your logo in a vector format, you can use that file for a business card or for a billboard and the image quality will be the same. Common vector file types include .AI, .EPS, .PDF (sometimes) and .SVG files.

So what is a raster image?

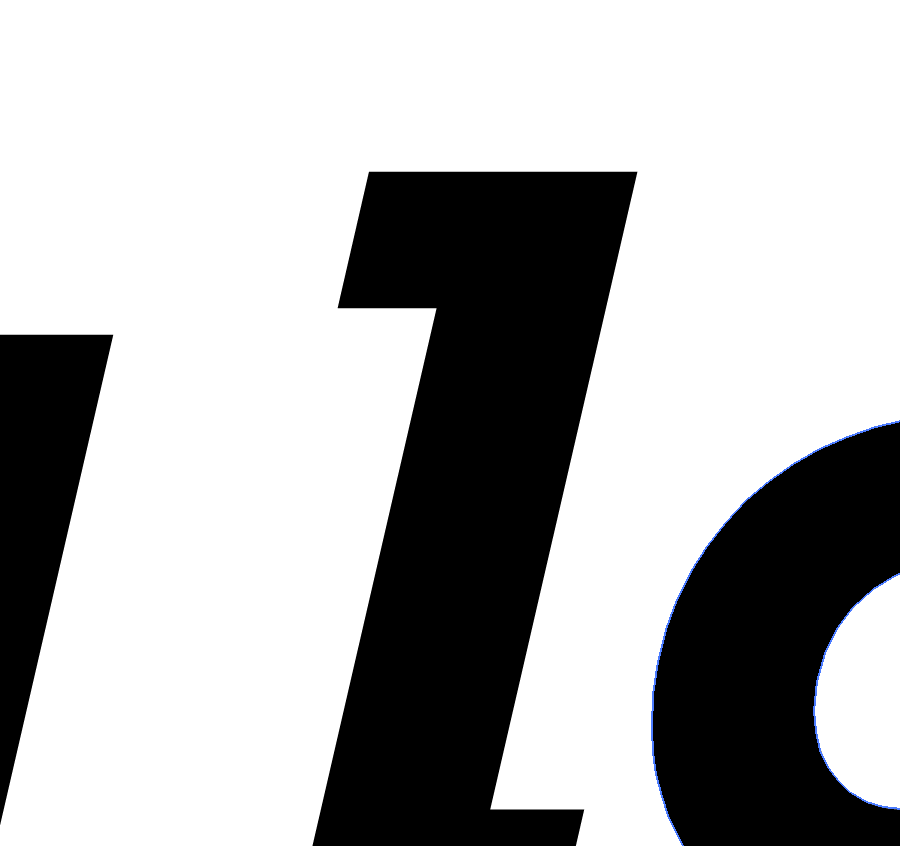

A raster image is built of small blocks of color. When scaled up those blocks are scaled as well and look pretty rough, especially on curves.

Put simply, raster images are built out of blocks of color (pixels), and vector images are built out of a series of mathematical instructions. A raster image only contains enough information to display the image of a logo (or a cat, for most of the internet) at a certain size. If you display that raster image at a larger size than it was created to cover, it begins to appear as blocks of color rather than smooth shapes.

Pixels: Little blocks of color

Most images used by most people are raster images, and are pixel-based file types. The raster image file types that I use on a daily basis are GIF, TIF, PSD, RAW, JPG, and PNG. Each one was developed for a different reason and each file type has it’s own hidden superpower. (Some were developed in an unsuccessful attempt replace the others.)

GIF

The Graphics Interchange Format, or GIF, was one of the earliest image formats but is still a mainstay of the visual internet. Of all the schisms in the design world, the divide over the pronunciation of this file type is possibly the most bitter. This might be the best answer.) Limited to 256 colors, the GIF can’t display images in a way that takes advantage of the full range of most modern screens. That limitation, along with a patent issue, was one of the main reasons for the development of the PNG format. Unlike the other file types listed here, GIFs can be strung together into short video animations. Animated or still, the humble GIF remains one of the most common image types on the internet. Avoid using GIFs in print, though–especially the animated ones. That’s just not going to work.

Superpower: Movement. GIFs can be animated, creating compelling or inane little repeating videos.

[Update: Front-end web developer Sara Soueidan recently put together a deep dive exploration into the ways that the SVG format is overtaking GIF in many of the capabilities that until now made the GIF indispensable.]

TIF

Tagged Image File Format is a less common image type, but it’s a powerful tool in the toolbox. The TIF is a “lossless” file format, meaning that no image information is lost when saving. TIF images can also be layered like a PSD, and can contain vector clipping masks making them an ideal format for high resolution print production. The downside of all that uncompressed information is that TIFs are often massive files, and can’t be read by many devices and users.

Superpower: Memory. The TIF is a high resolution, lossless image format. Also layers!

JPG

The JPG (or sometimes JPEG) is named after the Joint Photographic Experts Group who created it and is one of the workhorse image types in use today. It’s the default image type created by digital cameras and is used widely both in print and online. The JPG is capable of rendering images in a “Lossy compression”, and this compression is both its strength and its biggest weakness. (Let’s all reflect for a moment on this metaphor for the dual nature of our own strengths and weaknesses. Great–on we go.) These images show both the advantages and downsides of the JPG compression:

This image (with the same pixel dimensions) when compressed from 5.6 megabyte (on the left) is 900kb (center) and 185kb (right). In the context of a complicated image, especially in high contrast images, the compression artifacts are not as apparent, and the savings in terms of file size might be worth the quality loss in some situations.

If this image were going to be used at larger scales, the artifacts would be distracting.The JPG compression algorithm is especially harsh in areas that should be smooth gradients and subtle variations in color.

Even in a simple gradient the way that the compression algorithm averages areas of color creates banding at first and then large unsightly blocks of color at the extreme end.

Superpower: Adaptability. Variable compression and a jack of all trades. When in doubt, use a JPG–they’re versatile and can be viewed by most users on most devices.

PNG

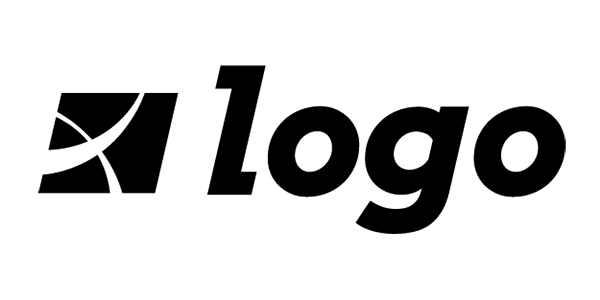

Portable Network Graphics, or PNGs, have most of the same capabilities as the JPG format with a few key distinctions. First, PNG image compression is “lossless”, meaning that the image quality doesn’t degrade every time you save the file. Second and more importantly, the PNG format supports transparency. This fact alone is one of the reasons for the PNG’s popularity on the web. The first image here is a JPG, 600px x 300px at 150ppi (pixels per inch), and there’s nothing wrong with the image, especially if you like white boxes around your logos. The second image is a PNG, also 600px x 300px at 150ppi.

Both the images are the same resolution and present colors and gradients equally well, but the PNG file type allows for a transparent background. No unsightly white boxes, thank you. Transparency and lossless compression have made the PNG one of most commonly used image formats on the web today. PNGs were not originally intended for use in print and although that distinction seems to be breaking down they are best reserved for use in designing for the web. (For even faster load times, use a compression service like TinyPNG to shrink your PNG images.)

Superpower: Invisibility. PNGs can have transparent backgrounds.

RAW

The RAW format is not as common for most casual image users, but it’s a go-to file format for serious photographers. Digital cameras are essentially little computers equipped with a lens and a sensor. The lens can gather infinite amounts of information, and the sensor receives and allows the processor to record some fixed amount of that information. Even in a simple image, there is a vast amount of information available—the amount of light, the tone and color of the light, the degree of detail present, etc. When those images are recorded as JPGs, the default for most cameras, the majority of the visual information the lens and the sensor gather are discarded. This creates a manageable file size and still produces a decent image.

The advantage that the RAW format has is that it records and retains a much larger range of that original image. The photographer can then access that original information later when they are processing the photo. If the captured image was too dark, or if the white balance was off, they can adjust those settings almost as if they were retaking the photo.

Superpower: Time travel, basically. RAW files contain scads of information from the moment the photo was taken, allowing photographers to go back and “retake” the photo using different settings.

PSD

The Photoshop Document, the mighty PSD, is the godfather of all other image types. You begin by defining the resolution and the size of your document in pixels, but there the line between vector and raster image begins to blur a bit. Adobe Photoshop, and therefore the PSD format, has gotten more and more complex–recent iterations of the program handle vector graphics (as “Smart Shapes“). Users can compose and create just about any image they can dream up. Users can edit a PSD in layers (and layers and layers and layers) so it’s easy to go back and edit and compose with separate elements and effects. They can also have transparent backgrounds.

Photoshop documents are only accessible to users who have, well, Adobe Photoshop, but once the composition is made those images can be exported as any of the other file types. There’s a good chance that many images in circulation have spent time as a PSD at some point in their story. For designers, the PSD’s capabilities make it the ideal vehicle for most image art assets.

Superpower: Composition. PSDs can contain layers, which allow the designer to arrange, combine, and process each element individually.

PSB

The Photoshop Document we just talked about is pretty amazing, but it does have its limitations. One of those limitations has to do with the image’s size. A PSD can only be a maximum of 2 gigabytes, which is usually plenty of digital elbow room for most projects. There are times when you have to go beyond that, especially in large format and grand format printing, and for that you’ll have to convert your PSD to a Large Document Format, or PSB. (PSB may actually stand for “Photoshop Big”, which sounds ridiculous, but is accurate enough–I think the largest single PSB file I’ve created was about 15GB.)

Superpower: Giant. PSBs can be massive, supporting images up to 300,000 pixels in any direction.

UPDATE: BPG and WebP formats

Someone brought this bit of image format news to my attention. The BPG format being developed by French programmer Fabrice Bellard may be a game changer, delivering JPG-quality images at half the file size, as well as better animations than GIFs:

BPG (Better Portable Graphics) is a new image format with the purpose to replace JPEG image format when quality or file size is an issue.

Browser support is still limited for the new BPG format, and it’s going to be competing in the same space as Google’s experimental WebP format:

WebP is a new image format that provides lossless and lossy compression for images on the web. WebP lossless images are 26% smaller in size compared to PNGs. WebP lossy images are 25-34% smaller in size compared to JPEG images at equivalent SSIM index. WebP supports lossless transparency (also known as alpha channel) with just 22% additional bytes. Transparency is also supported with lossy compression and typically provides 3x smaller file sizes compared to PNG when lossy compression is acceptable for the red/green/blue color channels.

Webmasters and web developers can use the WebP image format to create smaller and richer images that can help make the web faster.

WebP also supports animations although that capability is limited to users of Google’s Chrome browser. It’ll be interesting to see how the image format landscape looks in six months and beyond.

For more information on these image types, and to read about the more esoteric formats check out Adobe’s file format guide.

So what about vector graphic file types?

I’m working on an equally nerdy post about vector file types, which talks about the difference between them and which formats are best for which situations. (Why I often use .EPS files instead of .AI in my normal Illustrator workflow, for example, and how the .PSD blurs the lines between vector and raster images.)