A friend asked me a few days ago about the pros and cons of doing freelance design work along with your primary design job. Even though I approach the question as it relates to my work as a graphic designer, I think there are general principles here that apply to any profession.

The biggest benefits to pursuing side projects that I see relate to the variety of work. Along with my freelance work, I get to work with this solid group of people at MJM, and I’m fortunate that there’s a lot of variety even within MJM. (MJM spends about half its energy and time working for non-profit clients, and about half working with clients in vision care and related fields.) The more I thought about the pros and cons of working on outside projects as well, the more benefits I saw.

Working with a variety of clients, and therefore a variety of styles and voices, is one of the best ways to keep your mind and your fingers nimble. It may be the only way.

Everyone wins

A broad range of work is good for everyone involved.

Your clients (all of them) get work that is more sophisticated, informed by a wide range of past projects. When a designer works in one brand or one voice for a number of years, it’s easy to let everything have that flavor. On the other hand, if a designer is regularly working in several contexts, it’ll be much harder to fall into a creative rut.

But clients aren’t the only ones to benefit. Your employers will find themselves working with a designer who is much more versatile, able to adapt his or her style with an agility developed by constant practice.

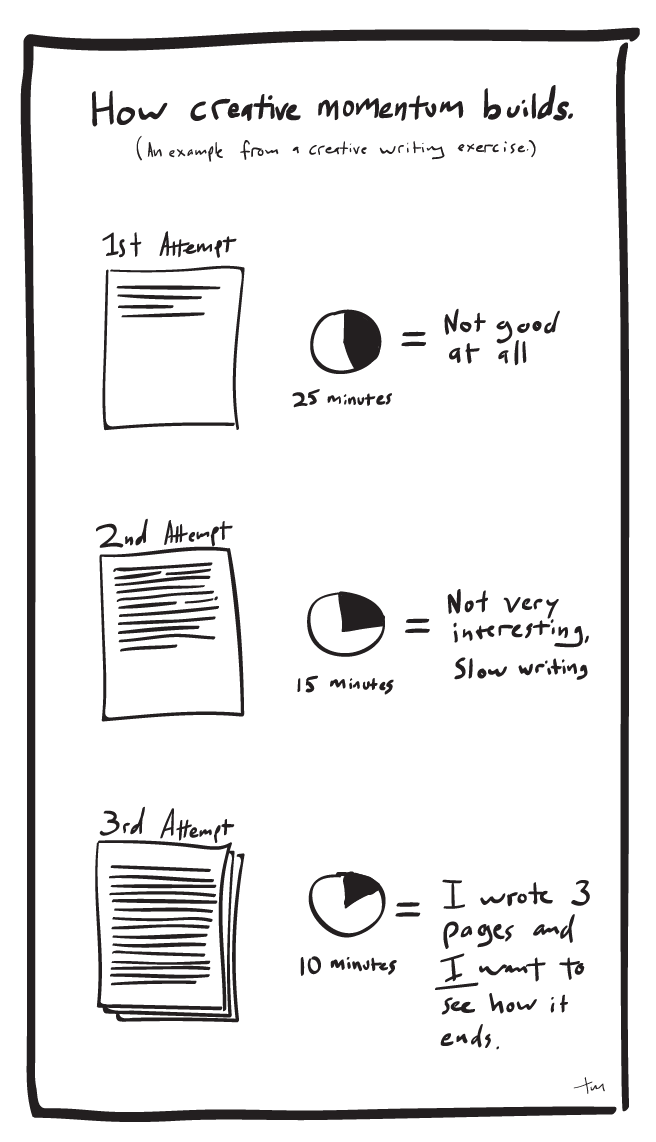

The designer may be the one who benefits most in the long run, in plain quality of life. None of us wanted to work in a creative field so that we could churn out the same work day after day. Working with a variety of clients, and therefore a variety of styles and voices, is one of the best ways to keep your mind and your fingers nimble. It may be the only way.

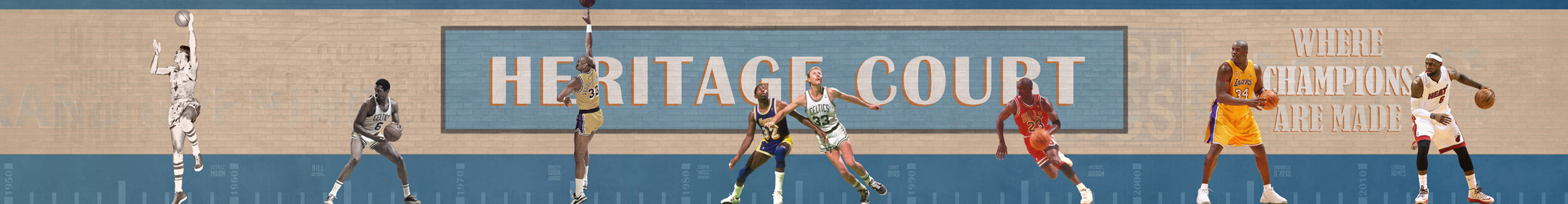

Access to a wide variety of styles

Working in a wide variety of projects give you access to a wide variety of styles and voices.

Along with our non-profit clients, MJM works with a number of organizations related to health care. The danger with health care design is that a lot of design in the industry ends up looking pretty similar. A lot of white space, clean, sparse layouts, blues and greens, nothing edgy or alarming (a lot like the interior of most hospitals, actually.) The value of having my hands in a lot of different projects is that each project influences and shapes the others. When I start designing a brochure for an eye care clinic, I may have just spent the morning developing a website for a non-profit, or laying out spreads for a cookbook. It’s likely, and I think beneficial, that elements of those projects will inform the clinic brochure. The clinic brochure will tend to be a warmer, more human, and more accessible piece than it would have been if I’d spent the morning designing other pieces for the health care industry.

Along with our non-profit clients, MJM works with a number of organizations related to health care. The danger with health care design is that a lot of design in the industry ends up looking pretty similar. A lot of white space, clean, sparse layouts, blues and greens, nothing edgy or alarming (a lot like the interior of most hospitals, actually.) The value of having my hands in a lot of different projects is that each project influences and shapes the others. When I start designing a brochure for an eye care clinic, I may have just spent the morning developing a website for a non-profit, or laying out spreads for a cookbook. It’s likely, and I think beneficial, that elements of those projects will inform the clinic brochure. The clinic brochure will tend to be a warmer, more human, and more accessible piece than it would have been if I’d spent the morning designing other pieces for the health care industry.

The same principle applies in the opposite direction. When I’m working on the website for the non-profit, I’ll be able to selectively apply some of the tone and visual language of the clinic brochure, helping to give the non-profit a credible, trustworthy voice. Even though the aesthetic might be less formal, the information still needs to be well-organized and easy to follow, and I can also draw from the tools that I used in the clinic brochure to do that.

Renaissance men and polymaths

Working in a variety of fields helps give you a broader understanding of each field.

Having worked on a variety of projects in various fields, I have a toolbox full of strategies and styles to choose from.

Part of our role as designers is to organize and present information in ways that are accessible to a wide audience. We’re not generally designing for other designers, or even for other people in our same demographic. To be successful, my eye clinic brochure needs to be equally accessible to a 20-something college student, a 55-year-old farmer, or a 35-year-old IT worker. Having worked on a variety of projects in various fields, I have a toolbox full of strategies and styles to choose from. But working on that wide variety of projects has also given me the opportunity to learn a lot about a range of topics.

In the spirit of the ideal Renaissance Man, a broad range of knowledge and experience makes it possible to make connections that might otherwise be missed. (Leonardo da Vinci was a painter, but also a sculptor, architect, mathematician, inventor, engineers, etc.) When we know and understand more, we are better teachers, and we’re better equipped to present information to our audiences.

The dangers

There are some dangers, of course. There’s a limit to how much you can keep track of in the one head you have, and the more clients and projects you have, there is always the increased chance of losing the thread on a particular project. There is also the potential for the occasional conflict of interest between your primary job and a freelance client, or odd political situations to be aware of, but an open line of communication between all parties and an ongoing dialogue with co-workers should avoid or defuse those situations.

––

Moving back and forth between several styles and voices allows a sort of cross-pollination between those projects. That interchange of creative ideas gives me as the designer ready access to more options than I would have had otherwise. (And often speeds up the process, which is always a welcome thing.)

If nothing else, your freelance design projects are a place to explore new ideas and learn new skills without asking permission or risking the credibility of the agency you work for.

Creativity, Design