The cheap book: crime broadsides, penny dreadfuls, and pulp fiction

The legacy of the cheap book

There was a time when a printed book was a treasure. Costly materials and the laborious process of copying and binding a book by hand meant that only well-off members of society owned any books at all, and only the wealthy had more than a few books. Not only was the physical book a precious thing—the ideas committed to the expensive paper and bound up within a book’s covers were themselves the product of years of thought. After thinking and developing their ideas, committing those thoughts to paper in writing a book was the culmination of a long and careful process.

Books as treasure: carefully written and difficult to produce

Books were once very difficult to produce. This made them very expensive and very rare. Books that were produced at this time would have been household treasures, protected and passed down to the next generation. The high cost of book production meant that only the most valuable texts were reproduced in book form. It was so much trouble to give language a durable physical form that book makers were very selective with what they decided to print.

Mass street literature: easy to produce, quickly written

If books were valuable when they were carefully written and hard to produce, the advent of mechanical press and the later ruthless efficiency of industrialized printing turn that equation upside down. The industrialization of book printing meant that books could be produced more cheaply. As the production of books became easier and cheaper, it meant that there was a much lower bar for the material that was worth printing.

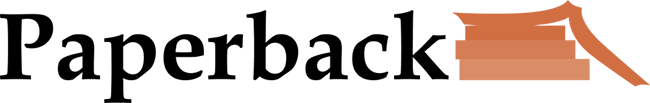

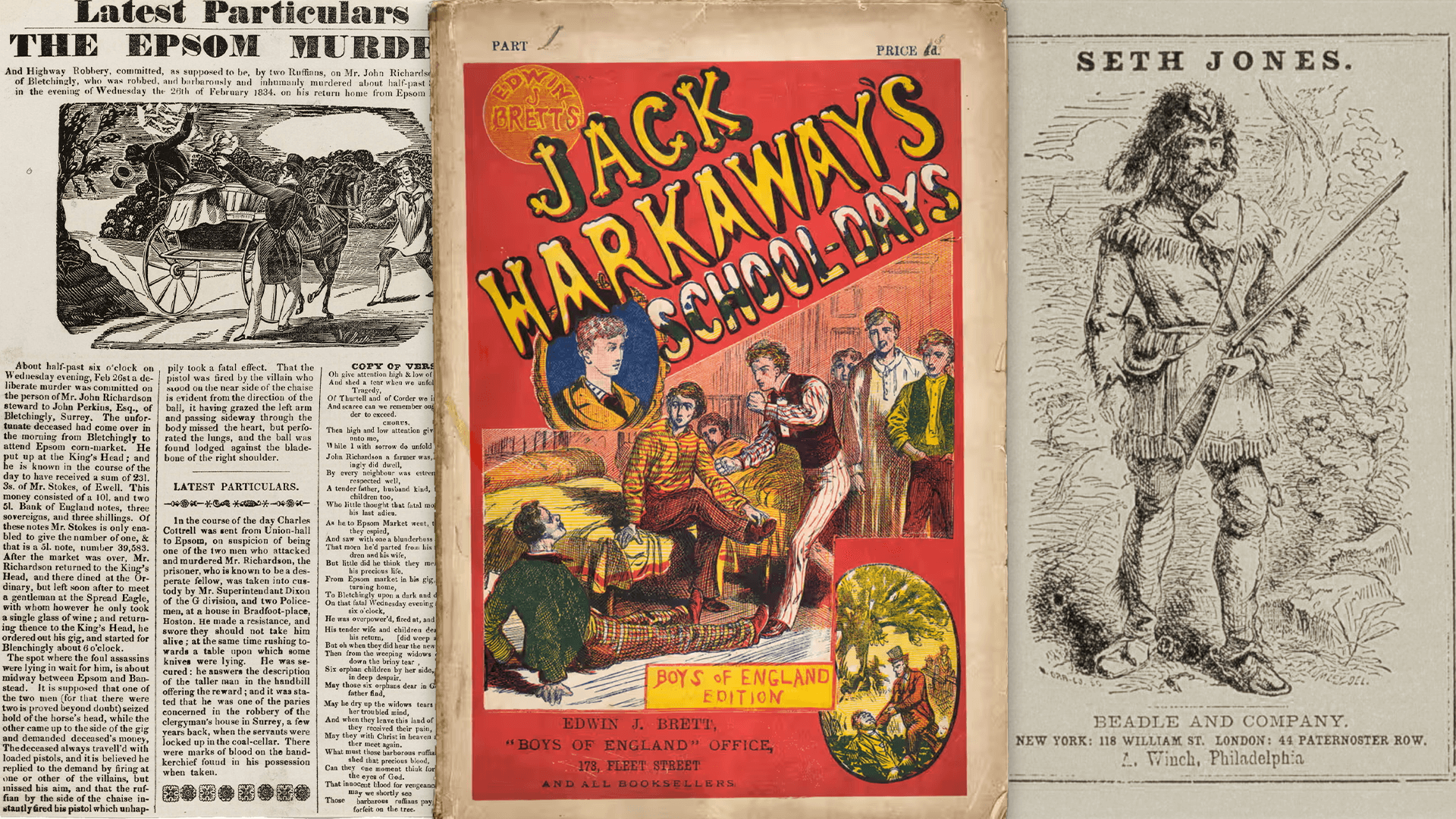

Crime Broadsides

In the 18th and 19th century, crime broadsides were a common form of printed media in the United Kingdom. A single-sided printed page, roughly the size of a modern 8 1/2 x 11 sheet of paper, these broadsides generally provided the details of the crime and the punishment that had been meted out. They often included a woodcut illustration, either a depiction of the crime or of the criminal’s execution. Cheaply printed and sensationally written, these broadsides were often sold at the public execution, but also had a larger reach:

Crime broadsides were also distributed across England and Wales by itinerant peddlers, far from the courts and gallows of the major cities and towns. They are one of the earliest examples of mass street literature.

English Crime and Execution Broadsides, Harvard Library Collection

In addition to sometimes lurid descriptions of the crime and trials, many execution broadsides featured the “dying speeches” or confessions and last words of convicts on the scaffold, sometimes in the form of poetry. Often there were warnings to would-be criminals. Increasingly, broadsides were illustrated with wood engravings, showing the execution scene or vignettes of the crime scene.

These broadsides, precursors to the mass newspapers that eventually eclipsed them, offered their readers a sense of the world beyond their own location and experience. They were presented to the reader as factual accounts, but as they became more popular there was an inclination to sensationalize the facts they presented. The appeal of the broadsides, the overall increase in literacy rates, and the ability to produce and distribute printed material on a large scale all contributed to the rise of reading as a new form of entertainment.

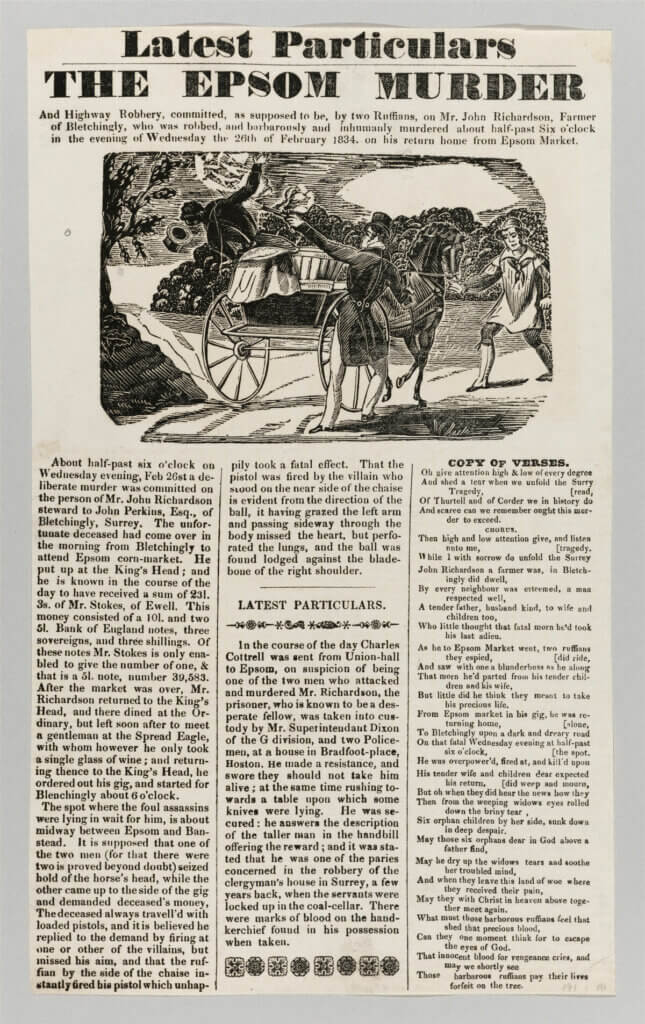

Penny dreadfuls

This appetite throughout mid-Victorian Britain for cheap, interesting reading material was answered in part by the “penny dreadfuls.” These were cheaply produced serial magazines that featured stories of adventure and travel, crime and detectives, and sometimes even early science fiction. They were so popular that between 1830 and 1850 records show there were nearly 100 publishers of penny fiction or penny bloods, as they were sometimes called. They varied physically, but seem to have ranged from 6 1/2 – 9 inches tall, printed on cheap paper with hastily done cover illustrations to catch the attention of potential readers. Most penny dreadfuls seem to have been between 8 to 28 pages, but since the stories ran through multiple issues, a single story would span many more pages. One archived exemplar at the British Library, Captain Macheath; or, the highwayman of a century since!, is listed on the library entry at “270 pages,” but notes that it was “published in 17 parts.”

By 1895, politicians and police alike were concerned about the effect these “immoral” and “escapist” reading materials were having on the those who consumed them. The penny dreadfuls were written in a way that primarily appealed to young men, and many reckless acts, violent crimes, and even suicides were attributed to the influence of type of fiction on this impressionable demographic. After a particularly troubling crime was committed in 1895 by two boys who had been reading these materials, calls were renewed to ban the popular penny dreadfuls, but those efforts came to nothing:

That summer several newspapers echoed the inquest jury’s call to ban penny dreadfuls, but the home secretary reminded the House of Commons in August that an inquiry of 1888 had been unable to establish a connection between cheap books and juvenile crime. Though penny dreadfuls were continually being discovered in the bedrooms and pockets of young criminals and suicides, this may have been only because they were in the bedrooms and pockets of most boys in Britain.

Penny dreadfuls: the Victorian equivalent of video games, Kate Summerscale, 2016

Story Papers

“Penny dreadfuls” can also be seen as a British subset of the larger category of story papers. Sometimes described as “literary magazines aimed at children and teenagers” and sometimes “the television of their day, containing a variety of serial stories and articles, with something aimed at each member of the family.” The first well-known story paper was produced in Britain in 1832 and they seem to have been continually produced until at least 1967. They were “weekly, eight-page newspaper-like publications, varying in size from tabloid to full-size newspaper format and usually costing five or six cents.” (For more, read George Orwell’s 1940 essay “Boy’s Weekly”, and look at the American legacy of story papers as well.)

Dime Novels

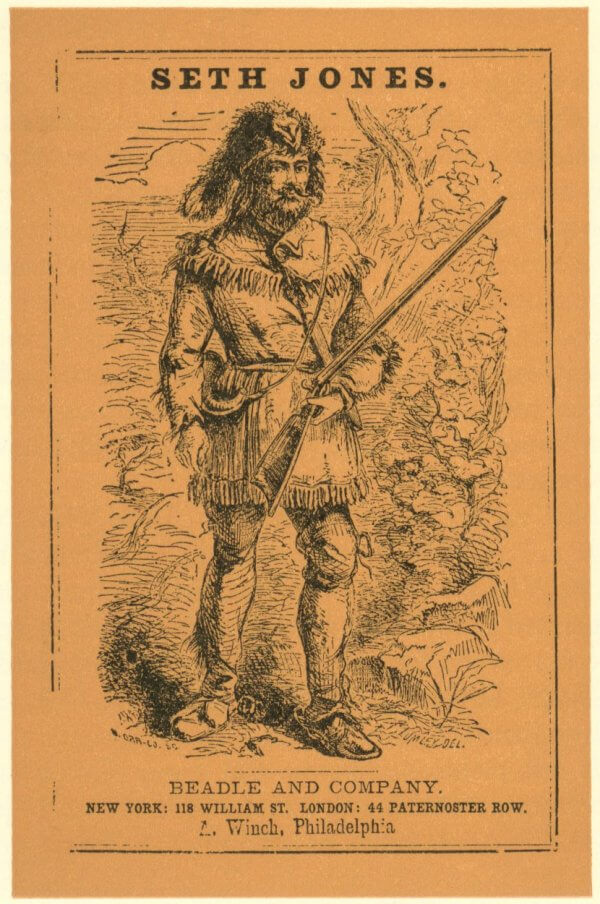

Cover of Seth Jones; or, The Captives of the Frontier by Edward S. Ellis (1860)

A number of popular story papers in America later provided content for a new class of mass literature. In a (barely) United States on the brink of the American Civil War, Beadle’s Dime Novels were first published in 1860 by Erastus and Irwin Beadle. The books in the Beadle series were small by modern standards—about 6 1/2 x 4 1/4” and 100 pages—and very simple: “The first 28 were published without a cover illustration, in a salmon-colored paper wrapper. A woodblock print was added in issue 29, and the first 28 were reprinted with illustrated covers. The books were priced, of course, at ten cents.”

Publishers printed (and reprinted) these dime novels in a variety of formats, and confusingly sold them for prices ranging from 5 to 15 cents. Generally each book was a standalone story, but series of stories following an established cast of characters grew more and more popular.

Pulp magazines and pulp fiction

Dime novels were cheap to make, but the pulp magazines that eventually edged them out were even cheaper. Every history of the pulp magazines begins in the early 1880s with a man named from Augusta, Maine who moved to New York to start a magazine. Frank Munsey had been working for several years to gather capital and manuscripts to begin publishing a periodical literary magazine, and in December 1882, The Golden Argosy published its first edition—8 pages long, selling for five cents a copy. By 1887 it would have a circulation of 115,000. The magazine was published continuously from 1882 until 1979. It did switch from weekly to monthly for some seasons, and under several variations on the original name, eventually settling on simply Argosy. It merged with several other magazines along the way, sometimes incorporating the acquired magazine’s name for a few issues. The All-Story Weekly was a significant one of these acquisitions, especially for fans of science fiction.

Among the many changes in Argosy’s format, two of the most historically significant happened in 1896. In October, the magazine became the first magazine to print only fiction, and the December issue was printed on cheap wood-pulp paper, making it the first pulp magazine. (The December issue was also the first Argosy issue to feature science fiction.)

As a book designer, I’ve often told clients that the cover of their book makes promises that the reader expects the interior to fulfill. Book publishers—those components of the publishing mechanism who are mostly keenly aware of the financial equation—generally think of the cover art primarily as a poster or advertisement to sell the book to potential readers.

Pulp fiction artists were in an odd position in what we think of as the normal flow of book production. In an era of cheap printing and cheap writing, the cover art was such a large part of the marketing of the book that the written content was often created to support the cover artwork:

“Pulps were most known for their exploitative fiction and controversial cover art. Pulp covers were always on higher quality paper and were usually high contrast and brightly saturated colors. The cover art on pulps were so important to the publication, that often times the art was actually made first. After it was made, it was then shown to the authors to come up with the magazine’s content based on that cover artwork.“

Mai Ly Degnan, Pulp Magazines and their Influence on Entertainment Today (nrm.org)

The legacy of the cheap book

As interesting as the history is, these forms of printed matter also contain a lot of problematic material. From the early crime broadsides, publishers were presenting the worst things that had happened in a community as entertainment disguised as news. The penny dreadfuls relied on the macabre and the weird to sell their issues, and readers who were looking for adventures beyond everyday life were drawn to the strangeness and alien quality of the stories they told. The pulp magazines, with their dependence on quick writing and cheap production had no qualms about relying on exploitative imagery and racist tropes to appeal to their audiences.

I’d like to look more into the legacy of these forms of cheap mass literature. There are clearly some lines of descent from the penny dreadfuls with their heroes and villains and adventures to the comic books you can pick up today. There also seems to be a clear line to be drawn from the crime broadsides to the sensationalized crime reporting presented by networks like Fox News, or the Unsolved Mysteries series of the 1980s and 90s, or the current interest in true crime podcasts. My own childhood was full of a series of the “Illustrated Classics Editions” from Moby Books. (Moby Dick was one of the titles in the series, and I never appreciated the publisher’s name or logo until researching for this article.) Looking at them now, I can see some echoes of the pulp tradition in these illustrated and heavily abridged classics.

To read more articles like this visit: Uncategorized