Cultural Density and The Midwest Small Town Inferiority Complex

I’ve been thinking for some time about a phenomenon I’ve called The Midwest Small Town Inferiority Complex. I’m in the market for a catchier name, but the complex can be summarized in the following axiomatic statements:

- Talent flows into big cities

- Talent migrates toward the coasts

- Therefore, anyone in a small town is either a) not talented, or b) is on their way to a large city or a coast

As a person who lives and works in a small midwestern town, I would like to think that the situation is more complex, and that talented designers doing good work can be found even in the hinterlands. I do think it’s possible, but I think that time, mathematics, culture, and human nature itself are working against me. The main points in the case against flyover country go like this:

- Humans enrich the places where they spend time.

- Humans build on existing culture.

- Culture building is a function of multiplication, not addition.

- More humans in one place equals more culture.

- Longevity of occupation equals more culture.

- More people over longer periods of time equals more culture.

- Large cities have cultural gravitational pull

1

Humans enrich the places where they spend time

We have a natural tendency to make our mark on whatever we find. Sometimes that human tendency is destructive—children drawing on walls, or teenagers carving graffiti into picnic tables, or tourists sticking gum to national landmarks. But often that natural inclination to shape our spaces leads to improvements or even beauty. On the few times that I’ve gone camping and stayed in the same place for several days, I’ve noticed that there is a gravitational pull toward improving an otherwise wild place. We make a ring of stones to contain the campfire, which leads to a pile of sticks near the fire pit, and maybe we gather a few logs to sit on. Underneath the tent site, we clear out any stones and flatten any particularly lumpy parts of the earth. Even beyond the purely pragmatic changes we might make to a wild place, there are often traces of human activity that are purely aesthetic—a walking stick with a carved handle, or a geometric arrangement of sticks, or a handful of wildflowers gathered and left at the fire pit for the next campers.

C. S. Lewis observed that, “Man is a poetical animal and touches nothing which he does not adorn.” (Is Theology Poetry? essay, 1962) (Lewis was likely alluding to (and expanding on) Dr. Samuel Johnson’s 1774 epitaph for poet Oliver Goldsmith.) While there are too many instances of human occupation degrading an environment, there are also countless marvels in the built environment that show that our general tendency is to improve and enrich the spaces we occupy.

2

Humans build on existing culture

Ideas have a combinatorial nature—technological innovations like Gutenberg’s press or the Wright brothers’ airplane were the product of many component advances brought together, and artistic movements like Cubism or the Bauhaus were the result of many artists and designers working and thinking together. Those interactions were multiplicative, not additive. Systems thinkers are fond of pointing out that “the whole is more than the sum of its parts.” [Some would choose to phrase it, “the whole is different than the sum of its parts.”]

3

The mathematics of culture building

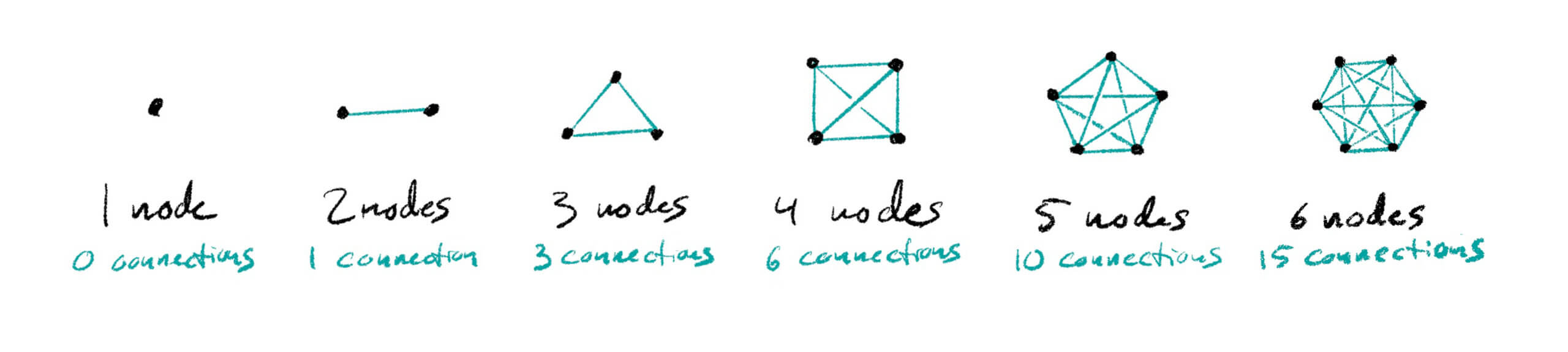

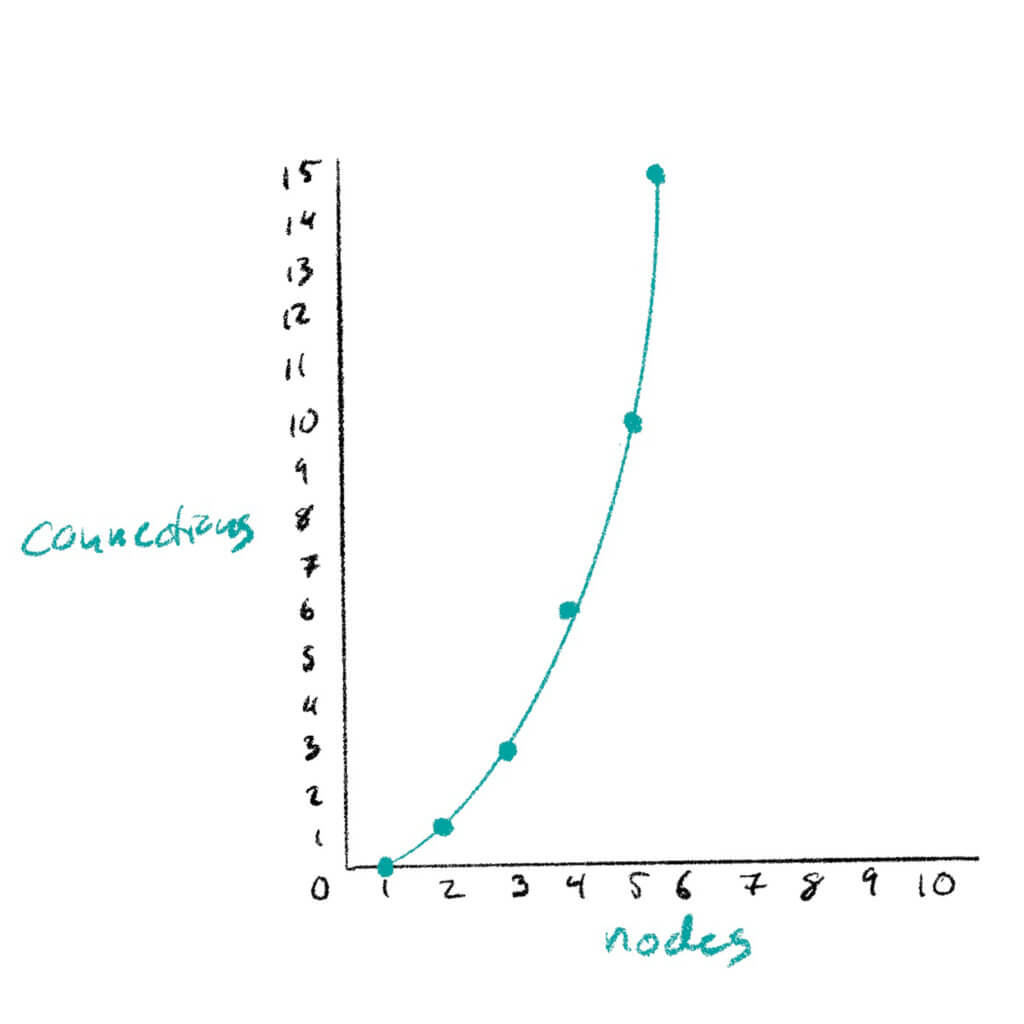

Network effects and Metcalfe’s Law

Robert Metcalfe originally developed his principle of network theory as a way to sell ethernet connections in the 1980s. In an interview, he said,

“Metcalfe’s Law began its life at about 1980 as a sales tool [in presentations] for my company to sell the Internet—specifically ethernet, which is the plumbing of the Internet—to customers. And this slide basically said that the cost of a network goes up linearly as you put the nodes on the network, but the number of possible connections goes up faster than that. It goes up as the square [of the number of nodes, that is, exponentially]. Then some years later in 1995, a young man named George Gilder was impressed with the idea and he called it Metcalfe’s Law, which basically says that ‘the value of a network goes up as a square of the number of users or attachments.’ So it’s an attempt to quantify the Network Effect.”

Dr. Robert Metcalfe, 2018

As nodes on a network are added linearly—one at a time—the value of the network increases exponentially. One person with a telephone is of no value, because no connections are possible. Two people with telephones starts to make sense, because there is now a single possible connection between the two people, or network nodes. Adding one more person to make this a network of three phones means that three possible connections can now be made. And adding a fourth person means there are now six possible ways that calls can be made, and so on into the stratosphere.

This theory means that every single node added to the network increases the value—the potential connections in that network—exponentially.

The many interconnecting nodes of human interaction that we call culture function similarly to a network. In a large city, cultural nodes like the tattoo shop, the art museum, the letterpress archive, and the dance studio don’t contribute to the city’s culture in an additive way—they contribute in a multiplicative or exponential way. The dance studio might stage a performance in the museum’s gallery, and the letterpress archive might prove to be a deep source of inspiration for the tattoo shop. Together those four “cultural nodes” are much more generative than the sum of their parts.

4

Population density equals more culture

Despite my hope that small towns can be home to greatness, I do think there is an undeniable reality that cultural richness is a product of population density. I mentioned above the combinatorial nature of cultural advances, and the network effect where each node makes the network exponentially more valuable. Those two considerations on their own point to large population centers having an advantage when it comes to culture building, and they seem to be firmly rooted in statistics and history. Add to that hard science something that sounds a little more mystical: the Water Cooler Effect.

Researchers at Harvard wanted to see how the productivity of collaborators was affected by their proximity—being physically near each other. They sifted through a large number of research papers to see how strong their research was, mapped against which study authors worked in the same building:

“Our data show that if the first and last authors are physically close, they get cited more, on average,” says research assistant Kyungjoon Lee. As that distance grew, citations generally declined. On average, a paper with four or fewer authors based in the same building was cited 45 percent more than one with authors in different buildings—“So if you put people who have the potential to collaborate close together,” he says, “it might lead to better results.”

The implications for culture growth are clear. The culture-building creative leaps rely on serendipitous collisions between unsuspecting passers-by just as much as they rest on talent and hard work. And cities are great at providing opportunities for collisions between unsuspecting passers-by.

5

Culture builds over time

At the heart of the University of Missouri campus in Columbia is Memorial Union, a gothic building with a large central arch that serves as an entrance to its two wings and crowned with four spires. The principal section of the building was completed in 1926 as a memorial to those who were killed in The Great War and it has served as the student union ever since.

My parents and I all attended the University of Missouri, although separated by about 30 years. (My mother went back to school later in life and completed a masters degree in counseling and a doctorate in psychology from the University of Missouri. We overlapped one semester—I was a freshman the semester she finished her PhD.) I remember my mom once she told me that as an undergrad in the early 70s she noticed the marble steps in Memorial Union were worn down in the center from years of student feet. She told me that her first impulse was to avoid walking where the steps were worn, so as to not contribute to the wearing.

After a year or so at the school, she changed her mind. She decided to walk in the scooped out part of the steps, in order to contribute to the legacy of the many feet that had walked on those stairs. I thought of her every time I walked on those steps, literally following in her footsteps. Together we shape the places we spend time, and the more human interactions concentrated in one place, the more those places are shaped.

There is a freshness and a grandeur in the wild and untouched places in the world–a few hours’ drive from where I’m writing the Badlands of South Dakota present a stunning natural spectacle. But that empty landscape and uncultivated hills don’t have much in the way of culture. I don’t mean that as an elitist critique—I mean that culture is a function of human interactions over time, and South Dakota is one of the most sparsely populated areas of the country. The relatively light human presence is why the land is mostly a pristine wilderness and also why there are not many cultural institutions.

Looking at Babylonian ziggurats, or Aztec and Mayan pyramids, or even archeological excavations in modern European cities you get a sense of a slow layering of years upon years of human interactions, creating more and more intricate webs of tradition and heritage and art. That cultural complexity is a product of the long layered years of interactions among generations of inhabitants, each generation building on what had come before. Cultural richness builds over time.

6

Population x Time = Culture

It’s surely not as simple as that pithy equation, but there’s a pretty strong case that says that a large city that has been established for a long time will provide a fertile ground for creativity and cultural innovation. There are certainly counter-examples—large cities with long histories that for a variety of reasons seem to be cultural dead zones

7

Large cities have cultural gravitational pull

Talented, creative people seeing to learn and grow and be challenged in their craft will always gravitate toward others like them. Designers will move to work where those people and studios are, and the large cities are mostly where they are found. Higher pay, more prestige, and more interesting work are most likely going to be found in larger markets.Big budgets and prestige projects also go to large and prestigious agencies, and to the victor go the spoils in terms of new projects and talented designers.

This isn’t a new phenomenon—some 700 years before Christ the author of Proverbs wrote,

Do you see a man skillful in his work?

He will stand before kings;

he will not stand before obscure men.

To the extent that the internet and remote work has flattened all the world into one large Zoom call, “anyone can work anywhere, from anywhere,” but the reality is that we will always be physical creatures, and the best place to spark a new idea or meet a new collaborator is going to be some version of the local letterpress poster archive or the office water cooler.

“Bloom where you’re planted?”

Or should it be, “Love the one you’re with”? If there is a tidy conclusion to this article, I haven’t yet grown wise enough to know it. It’s true that the complex alchemy of human interactions that happens in larger cities over time yields considerably more “culture” than places where humanity is more thinly layered. It’s also true that each single human on the planet is an infinite and complex world, if you take the time to know them. I’ll close with a recommendation from a friend to spend a few minutes listening to author and podcaster John Green tell about how he came to appreciate the richness of a seemingly drab and uncultured place. (h/t @tenley.s) I suspect that, just like with human relationships, what we “get out” of a place has a lot to do with how much we allow ourselves to know and love it, and how much we give to it.

To read more articles like this visit: Uncategorized